Want to experience the greatest in board studying? Check out our interactive question bank podcast- the FIRST of its kind here: emrapidbombs.supercast.com

Author: Sam Hopp, MSIII

Peer Reviewers: Travis Smith, DO, Blake Briggs, MD

Introduction

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is a clinical syndrome characterized by an acute kidney injury with associated microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Infection with Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (also known as STEC) is the most common cause of HUS in the pediatric population, accounting for up to 90% of all cases in children under the age of five. The most common strain of STEC-HUS is E. Coli O157:H7, with a primary means of transmission through undercooked food (beef) and less common sources, including person-to-person or direct animal contact.2,3 Children are more affected than adults, and the causes, diagnosis, and management are essentially the same for adults and children, so we will essentially speak regarding the care of children this review.

HUS can also be classified into both acquired and hereditary causes. STEC-associated HUS mentioned is a “typical” secondary cause of HUS. Other culprits in this category include Strep pneumoniae, HIV, drug toxicities, pregnancy, or autoimmune disorders, including lupus.4 Primary or “atypical” HUS is a hereditary syndrome often due to complement gene mutations, antibodies to complement factor H, diacylglycerol kinase epsilon gene mutations, or inborn error of cobalamin C metabolism.4

It’s important for us to cover this acquired HUS, as its often misdiagnosed. In fact, one study showed that in children with STEC, 1 in 7 developed HUS within a median of 3 days, and ~30% of those who had HUS were first sent home.5

Annoying, but necessary, pathogenesis

Welcome back to medical school. Remember Shiga toxin? We didn’t think you did…. So, the virulence of STEC comes from the production of Shiga toxin. The release of Shiga toxin causes widespread microangiopathic injury and a reactive prothrombotic state. The prothrombotic state and high platelet consumption leads to the formation of intravascular microthrombi, which clog the afferent vessels of the kidneys and cause acute kidney injury. The microangiopathic hemolytic anemia results from the shearing of RBCs as they pass by microthrombi, leading to the characteristic schistocytes seen on a blood smear.

Clinical Presentation

Accelerate your learning with our EM Question Bank Podcast

- Rapid learning

- Interactive questions and answers

- new episodes every week

- Become a valuable supporter

The classic prodromal illness of children with STEC-HUS is abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea with or without a fever. The diarrhea is often non-bloody and turns bloody after 1-3 days. The initial illness typically resolves within a week, and complications of HUS (if occurring) arise 5-13 days after the initial onset of symptoms.

Patients presenting with pallor, decreased energy, oliguria, or edema in the setting of recent gastrointestinal illness are highly suspicious for HUS. Despite thrombocytopenia, there is rarely evidence of purpura or active bleeding. Additionally, up to 33% of patients with HUS may have CNS involvement, including AMS, seizures, coma, stroke, or hemiparesis.6

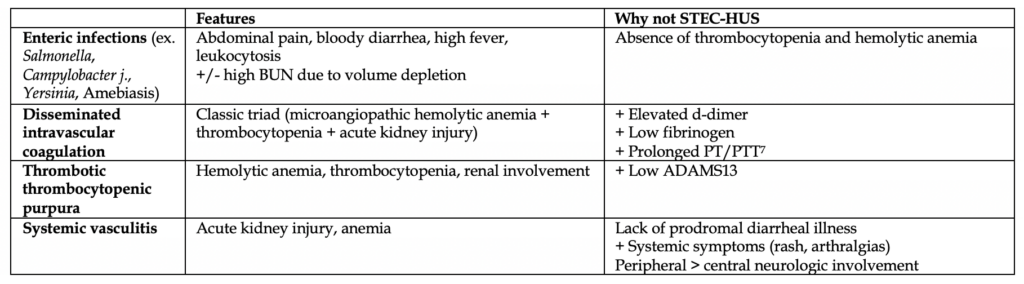

Look-Alikes!

Below are some pathologies that are often mistaken for STEC-HUS on board exams. Although management of these patients may not change much in real life, it’s important to note the differences here.

Diagnosis

The first step is a good history — suspect STEC infection in kids with acute onset of bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain or acute onset diarrhea with known exposure to STEC patient/outbreak.

Initial labs: CBC, electrolytes (including creatinine), urinalysis, stool specimen for culture or Shiga toxin test

– Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia:

– Hgb < 8 g/dL with a negative Coomb’s test (you won’t have access to a Coomb’s test in the ED)

– Peripheral smear showing up to 10% schistocytes and helmet cells

– Thrombocytopenia: platelet count below 140,000/mm3

– Acute kidney injury: variable presentation on labs, often abnormally elevated serum Cr and BUN, may have hematuria on urinalysis

– Coagulation studies to distinguish from DIC

Treatment

There is a positive association between volume depletion and reduction of adverse outcomes in volume-depleted patients.8 If the patient tolerates it, be aggressive with fluids. Monitor electrolytes closely, as there is likely to pH changes and fluid shifts from the profound diarrhea.

Anemia is a common complication due to the hemolytic anemia. Stay on top of this, and perform a PRBC transfusion when Hgb level < 6-7 g/dL or Hct < 18%.9 Emergent dialysis might be needed in critically ill patients.

But really, can I give antibiotics?

There is NO initial role for antibiotics. Studies have showed an increased incidence of HUS development in children with STEC when treated with antibiotics. A meta-analysis of observational studies with low risk of bias revealed a positive association of 2.24 between antibiotic use and HUS development (95% CI 1.45-3.36).11 In addition, a prospective study of 259 children < 10 years of age with E coli O157:H7 STEC found that HUS occurred in 36% of children who received antibiotics versus 12% in the children who did not.12 No studies have found that antibiotics reduce the symptoms or complications associated with STEC.13

Prognosis

Thankfully, this has a favorable prognosis, often resolution of hematologic manifestations in 1-2 weeks with the recovery of renal function shortly following. There is a 4% mortality rate from CNS injury (edema, infarct, or brain death), hyperkalemia, coagulopathy, sepsis, heart failure, or pulmonary hemorrhage.10 5% have long-term sequelae (often stroke or end-stage renal disease).14 Poor prognostic factors include: WBC >20k at presentation, persistent oliguria/anuria and prolonged dialysis, >50% of affected glomeruli on renal histology.15

References

1. Hemolytic uremic syndrome. Noris M, Remuzzi G. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(4):1035. Epub 2005 Feb 23. Transplant Research Center, Chiara Cucchi de Alessandri e Gilberto Crespi, Villa Camozzi, Via Camozzi, 3 24020, Ranica (BG), Italy.

2. Escherichia coli O157 Outbreaks in the United States, 2003-2012. Heiman KE, Mody RK, Johnson SD, Griffin PM, Gould LH. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(8):1293.

3. Sorbitol-fermenting Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H(-) strains: epidemiology, phenotypic and molecular characteristics, and microbiological diagnosis. Karch H, Bielaszewska M. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(6):2043.

4. An international consensus approach to the management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in children. Loirat C, Fakhouri F, Ariceta G, Besbas N, Bitzan M, Bjerre A, Coppo R, Emma F, Johnson S, Karpman D, Landau D, Langman CB, Lapeyraque AL, Licht C, Nester C, Pecoraro C, Riedl M, van de Kar NC, Van de Walle J, Vivarelli M, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, for HUS International. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(1):15.

5. McKee RS, Schnadower D, Tarr PI, et al. Predicting Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome and Renal Replacement Therapy in Shiga Toxin-producing Escherichia coli-infected Children. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:1643.

6. Acute neurological involvement in diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Nathanson S, Kwon T, Elmaleh M, Charbit M, Launay EA, Harambat J, Brun M, Ranchin B, Bandin F, Cloarec S, Bourdat-Michel G, Piètrement C, Champion G, Ulinski T, Deschênes G. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(7):1218. Epub 2010 May 24.

7. Marder VJ, Martin SE, Francis CW, Colman RW. Consumptive thrombo-hemorrhagic disorders. In: Hemostasis and Thrombosis: Basic Principles and Clinical Practice, 2nd ed, Colman RW, Hirsh J, Marder VJ, Salzman EW (Eds), Lippincott, Philadelphia 1987. p.975.

8. Associations Between Hydration Status, Intravenous Fluid Administration, and Outcomes of Patients Infected With Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Grisaru S, Xie J, Samuel S, Hartling L, Tarr PI, Schnadower D, Freedman SB, Alberta Provincial Pediatric Enteric Infection Team. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(1):68.

9. The hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kaplan BS, Thomson PD, de Chadarévian JP. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1976;23(4):761.

10. Postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome in United States children: clinical spectrum and predictors of in-hospital death. Mody RK, Gu W, Griffin PM, Jones TF, Rounds J, Shiferaw B, Tobin-D’Angelo M, Smith G, Spina N, Hurd S, Lathrop S, Palmer A, Boothe E, Luna-Gierke RE, Hoekstra RM. J Pediatr. 2015 Apr;166(4):1022-9. Epub 2015 Feb 4.

11. Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Infection, Antibiotics, and Risk of Developing Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Meta-analysis. Freedman SB, Xie J, Neufeld MS, Hamilton WL, Hartling L, Tarr PI, Alberta Provincial Pediatric Enteric Infection Team (APPETITE). Clin Infect Dis. 2016 May;62(10):1251-8. Epub 2016 Feb 24.

12. Risk factors for the hemolytic uremic syndrome in children infected with Escherichia coli O157:H7: a multivariable analysis. Wong CS, Mooney JC, Brandt JR, Staples AO, Jelacic S, Boster DR, Watkins SL, Tarr PI. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(1):33. Epub 2012 Mar 19.

13. Randomized, controlled trial of antibiotic therapy for Escherichia coli O157:H7 enteritis. Proulx F, Turgeon JP, Delage G, Lafleur L, Chicoine L. J Pediatr. 1992;121(2):299.

14. A 20-year population-based study of postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome in Utah. Siegler RL, Pavia AT, Christofferson RD, Milligan MK. Pediatrics. 1994;94(1):35.

15. Long-term outcomes of Shiga toxin hemolytic uremic syndrome. Spinale JM, Ruebner RL, Copelovitch L, Kaplan BS. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(11):2097