Want to experience the greatest in board studying? Check out our interactive question bank podcast- the FIRST of its kind here: emrapidbombs.supercast.com

Author: Blake Briggs, MD

Objectives: define endocarditis and its subtypes, review normal endocardial anatomy and physiology, discuss in detail the microbiological causes, diagnoses, and treatments of infective endocarditis, briefly identify neoplastic and autoimmune endocarditis.

Endocarditis: inflammation of the endocardium, most commonly the heart valves.

3 categories: infective, neoplastic, and autoimmune. Each of the 3 categories involve characteristic lesions forming on valve tissue. These are called “vegetations”. By far, infection is the most common cause.

Vegetations: valve lesion composed of fibrin, platelets, leukocytes, and microorganisms (if infective endocarditis).

Calcifications may be present if the lesion is chronic (>4 weeks old).

Normal endocardium

-avascular tissue: very limited ability to mount an immune response

-around 5L of blood passes through each heart valve every minute

Accelerate your learning with our EM Question Bank Podcast

- Rapid learning

- Interactive questions and answers

- new episodes every week

- Become a valuable supporter

-damages to the endocardium can increase the risk for organism colonization.

Infective Endocarditis

This condition is actually more common than many people think, and its incidence is increasing. As heroin usage continues to rise in the US, so will endocarditis. The mortality can range from 25-40% depending on how soon it is diagnosed and treated.

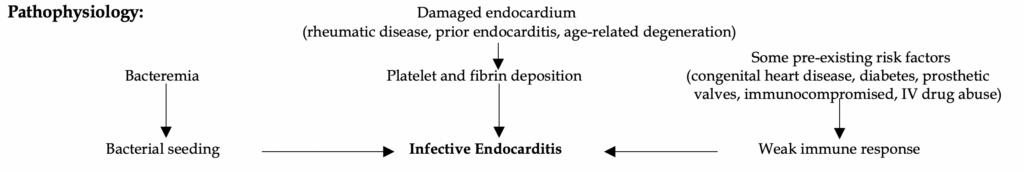

Bacteremia by itself does not cause endocarditis. There must be damaged endocardium and/or at least one pre-existing risk factor for infective endocarditis to develop. See our diagram below on the pathophysiology of endocarditis.

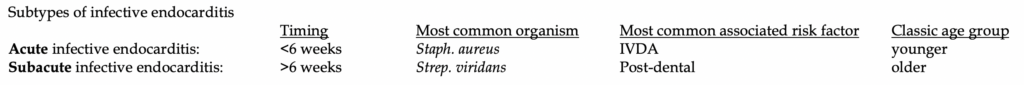

Presentation: Fever and a new murmur are by far the two most common symptoms of infective endocarditis. Fever is found in 90%, and a new murmur is seen in 85%. Patients can be classified into subacute or acute infective endocarditis, see below.

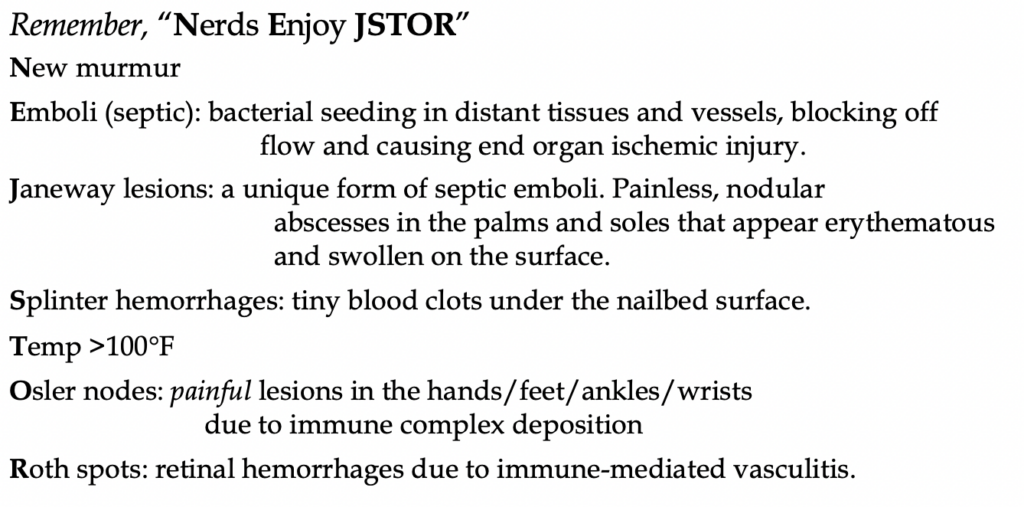

There is a good mnemonic we came up with to help remember the “classic” but rare findings of endocarditis.

How sick will they look?

Acute endocarditis: usually sicker with progression into shock and potentially even acute ventricular failure. Think Staph. aureus = worse infections.

Subacute endocarditis: Nonspecific symptoms, think Strep. viridans as less virulent as Staph. Fever, murmur, +/- tachycardia. Although rare, patients will more likely present with more of the specific lesions (Janeway, Osler, Roth spots), as mentioned above.

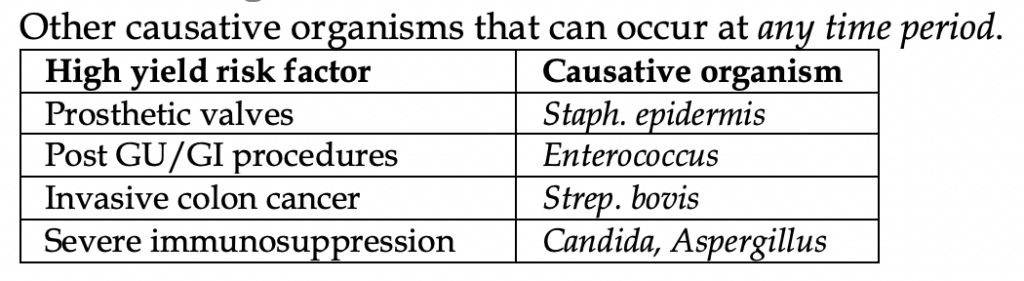

Other causative organisms are listed below in the table.

A note about right vs left endocarditis

Although IVDA is classically associated with right-sided endocarditis, left-sided seeding is still much more common overall (the mitral valve is the most common valve). However, when you see right sided endocarditis, IVDA is the likely cause until proven otherwise.

There are some differences between right and left sided endocarditis in terms of presentation, especially when it comes to emboli. In particular, right sided endocarditis has pulmonary septic emboli, while left sided endocarditis has systemic septic emboli such as stroke (most common), renal

infarction, mesenteric ischemia, and limb ischemia.

Diagnosis

Three sets of blood cultures should be drawn ten minutes apart. Other nonspecific inflammatory markers include CRP, ESR, CBC, and CMP.

The money is in the ultrasound. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is >90% sensitive and 100% specific, better than transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) (sensitivity ~75%, specificity 100%).

The Duke Criteria is helpful but no need to memorize. It is more on internal medicine boards and not emergency medicine.

When do you go for TEE after TTE? Anytime there is a positive TTE you should follow up with a TEE to look for more structural damage. This is especially important if the patient does not respond to treatment.

Another reason is a negative TTE but you have high clinical suspicion and/or positive blood cultures.

When to go straight to TEE? Prior valve abnormality, or limited windows due to body habitus.

You should also have a low suspicion to perform CT scans. Septic emboli can land in the lungs and brain (most commonly) but are also found elsewhere.

Causes of “Culture negative” endocarditis (occurs in <10% of all cases):

By far, the most common cause of negative cultures is due to prior antibiotic administration.

Another cause are slow-growing bacteria: HACEK bugs (Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella), Brucella, Coxiella, Aspergillus. (These bugs are extremely rare and cause <5% of all cases).

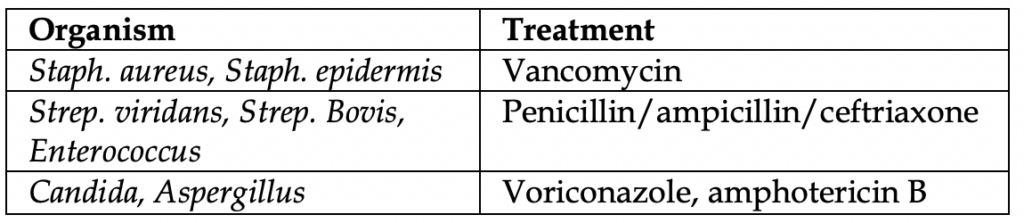

Treatment

For empiric coverage, only vancomycin should be needed (unless fungal cause is suspected). All are given IV, for 2-6 weeks on average.

Complications and Surgery

50% of patients will have some sort of chronic cardiac disability such as valve dysfunction or heart failure. Neurological symptoms are found in up to 40% of patients (e.g. stroke, IPH, abscess). 25% of patients have septic emboli elsewhere.

In less than half of patients, surgery will be needed to remove infected tissues, abscesses, and reconstruct the valve.

When surgery is necessary: acute heart failure is evident, fungal cause, persistent sepsis after 72 hours of therapy, aneurysm rupture, electrical disturbances found on EKG, septic emboli >2 weeks after therapy.

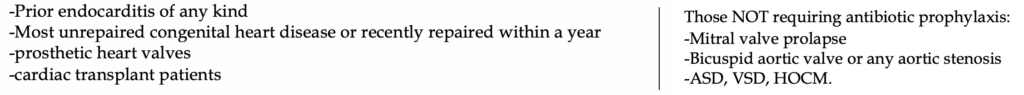

Prophylaxis*

Certain patients require antibiotics when undergoing endoscopies/colonoscopies, urinary tract procedures, or dental work due to their predisposed risk for developing infectious endocarditis. When antibiotics should be given is detailed below in the following table.

Antibiotic regimen: Amoxicillin 1 hour prior to the procedure.

*Note: these guidelines are currently being debated in the US and are no longer followed in the UK.

A quick word on nonbacterial endocarditis (Marantic endocarditis)

There are two causes, neoplasm and autoimmune disease.

Marantic is Greek for “wasting away”, which reminds us that nonbacterial endocarditis is not an acute disease, but one in which the patient chronically suffers from a comorbidity. The vegetations are “sterile”, meaning there is no bacteria (if that wasn’t obvious).

Causes: mural thrombus, metastatic cancer (especially adenocarcinoma), autoimmune disease

Systemic lupus is a classic board topic: Libman-Sacks endocarditis

-The unique thing about SLE endocarditis is that the vegetations are on both sides of the valve. That’s only seen in SLE.

-Treatment: steroids

The difficult part of diagnosing nonbacterial endocarditis is that the reliable symptoms from infective endocarditis are no longer present. No acute inflammation typically means no fever. Non-invasive, sterile vegetations often means no immediate murmur. Thus, patient history is critical to suspecting these causes. The lesions are often clinically silent until enough valve destruction causes clinical symptoms.

Look for the patient with no fever but a new murmur and history of cancer or SLE.

More commonly, the question will give you a patient who has SLE, and then the question will ask “what could the patient likely develop if lupus is left untreated?”