Want to experience the greatest in board studying? Check out our interactive question bank podcast- the FIRST of its kind here: emrapidbombs.supercast.com

Authors: Travis Smith D.O., Ryan Ferguson OMS-4

Peer Reviewer: Blake Briggs, MD

Introduction

Anorectal disorders can be…you know… a pain in the rear. But that’s okay because we got a great list of disorders to review to prevent yours from getting chapped. These disorders range from simple to complex and can manifest signs of underlying local or systemic disorders. Studying these disorders might make you a little anal retentive but this review should help loosen you up. Just remember that a focused history and careful examination are crucial.

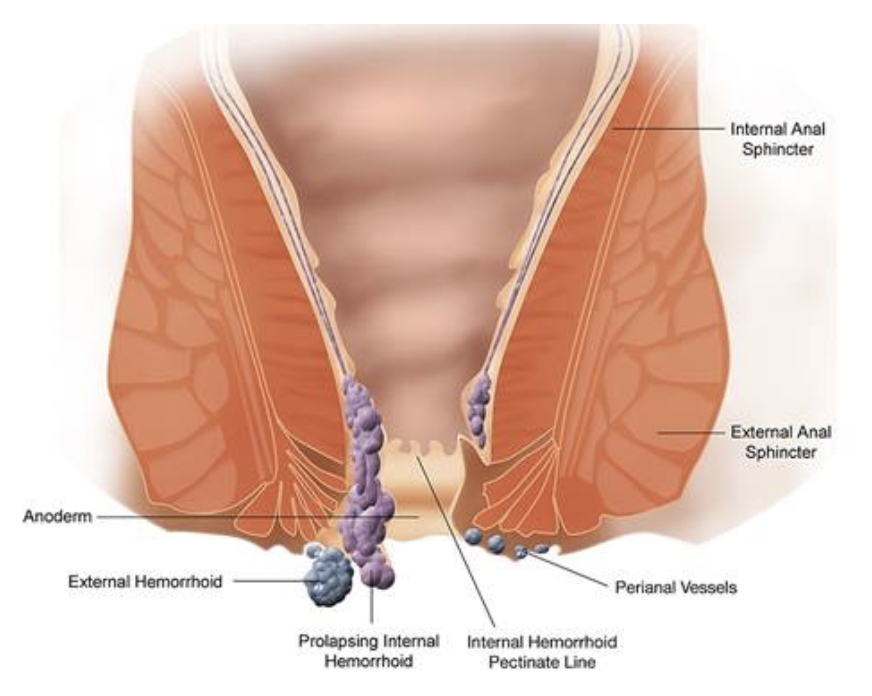

The image above shows the pathophysiology of internal and external hemorrhoids. (Image used with permission). You can refer to this photo throughout the document for reference.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis – Lateral or Sims position is most common position for digital rectum exam and anoscopy.

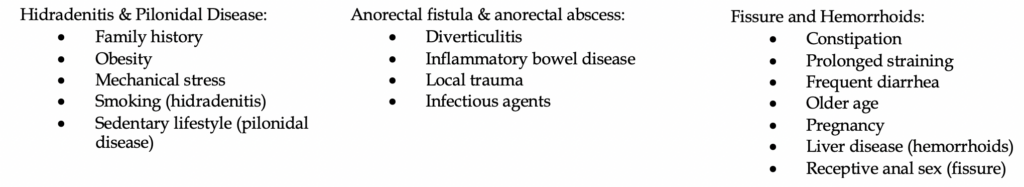

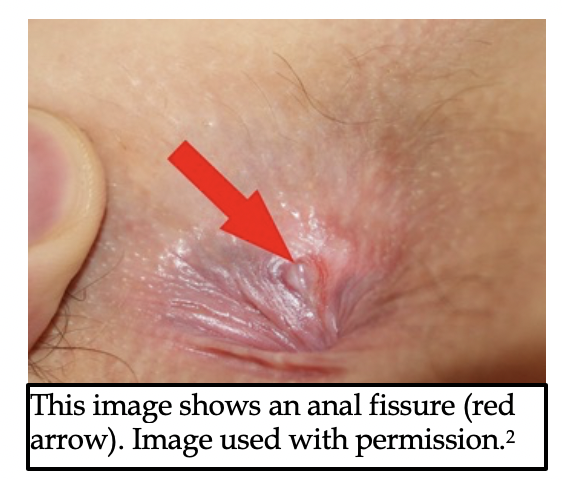

Anal fissure is a tear in the anoderm of the anal canal most commonly caused by the recurrent passage of hard stools or certain systemic diseases.

Presentation: sharp tearing pain occurs with defecation; subsides between bowel movements, bleeding is bright and in small quantities.

· Superficial linear tear of anal canal, most often posterior midline, 80-90% of cases. Fissure that is not midline is likely due to systemic disease. Muscle fibers are weakest in the posterior midline, and the blood supply is weak there as well.

Accelerate your learning with our EM Question Bank Podcast

- Rapid learning

- Interactive questions and answers

- new episodes every week

- Become a valuable supporter

· Rectal exam can be extremely painful and might not be possible without topical anesthetic agents. Topical 2% lidocaine jelly may provide some relief during exam.

Hemorrhoids- normal vascular structures that are located in the submucosal layer in the lower rectum. They arise from a cushion of dilated arteriovenous channels and connective tissue. Internal hemorrhoids are proximal to the dentate line and arise from the superior hemorrhoid veins. External hemorrhoids are located distal to the dentate line and arise from the inferior hemorrhoid veins.

Presentation: bright red blood on surface of stool, toilet tissue, or at end of defecation. All hemorrhoids are typically painless unless thrombosed. Irritation or itching of perianal skin is a common sign. Some may be prolapsed if large.

Internal hemorrhoids: graded based on the degree of prolapse from the anal canal: Grade I-IV, you don’t need to memorize the grades.

o Most important are grade IV: irreducible on exam and may strangulate.

External hemorrhoids

o Distal to the dentate line and arise from the inferior hemorrhoid veins.

o Highly innervated → painful when thrombosed…ouch!

Anal fissures and hemorrhoids are managed similarly. WASH Regimen: warm sitz baths, analgesia, stool softeners, high fiber diet

o hot sitz bath for at least for at least 15 minutes, 3 times/day and after each bowel movement.

o topical steroids and analgesic ointments may provide relief but do not help with healing

o bulk laxatives and stool softeners can help prevent future cases (avoid laxatives causing liquid stool due to risk of cryptitis and anal sepsis)

o high fiber, low fat diet. Increased water consumption (not soda or teas), regular exercise, and avoidance of constipating medications.

Recently thrombosed, painful external hemorrhoids (<72 hours of symptoms) can be treated with excision of the clot in the emergency department. After local infiltration with 1% lidocaine, an elliptical skin incision is made over the hemorrhoids and the thrombus is removed. Packing and pressure dressing usually control the bleeding. Pressure dressing may be removed after about 6 hours, when patient takes their first sitz bath.

NOTE: Excision of hemorrhoids should not be performed in the ED on immunocompromised, children, pregnant women, patients with portal hypertension, or those who are anticoagulated.

Anorectal abscess– is an infected anal crypt gland. Anal crypt glands (sounds like the most awful place ever) are present around the anal canal at the level of the dentate line. An obstruction can cause the anal gland to become infected, which promotes bacterial growth and abscess formation.

Presentation: Pain can be dull, aching, or throbbing, and becomes worse with defecation, but persists between bowel movements. Fever and leukocytosis may be present.

· Superficial tender mass, which may or may not be fluctuant. Most commonly location is close to the anal verge (lower edge of anal canal), often posterior midline. Ultrasound may be helpful, but clinical evaluation is often sufficient.

If a complicated abscess is suspected, obtain CT.

Simple, isolated, fluctuant perianal abscesses may be drained in the ED. Using proper procedural sedation and local anesthetic, a linear or cruciate incision is made. You can pack linear incisions with sterile gauze; packing is not needed with cruciate incision. Cover the wound with bulky dressing and have patient take frequent Sitz baths starting the next day. Antibiotics are not required. ED/PCP follow up in 24 hours.

All other perirectal abscesses should be drained in the operating room.

For elderly or those with fever or leukocytosis, diabetes, valvular heart disease, cellulitis or immunocompromised give broad spectrum antibiotics (piperacillin-tazobactam; or ampicillin/sulbactam) and obtain surgical consult.

Anorectal fistula- an epithelized tract that connects the anus or rectum to the perirectal skin. The fistula originates from an opened or ruptured perianal abscess that formed from an infected anal crypt gland. They are classified by their relationship to the anal sphincter by Parks’ classification and broken down to include superficial, intersphincteric, transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphincteric fistulas.

Presentation: usually a “nonhealing” anorectal abscess following drainage, or with chronic purulent drainage and pustule-like lesion in the perianal area. Intermittent rectal pain with defecation, sitting, and, if severe enough, even activity. Usually no fever.

· Diagnosis based on clinical findings: pain, purulent discharge and perirectal skin lesion.

· Imaging often not necessary, but may be helpful for complex or recurrent fistulas.

· Analgesics, IV fluids, antibiotics (piperacillin-tazobactam) and obtain surgical consultation.

Pilonidal disease– an infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that usually occurs at a different location than anorectal fistulas. It is usually found at or near the upper part of the intergluteal cleft due to an ingrown hair, which causes foreign body granuloma reaction.

Presentation: swelling, pain and persistent discharge located in the creases of the buttocks near the coccyx. An abscess may present as tender indurated mass with fluctuation.

· Diagnosis is clinical; imaging or laboratory studies are not necessary

· Incision and drainage, antibiotics only if cellulitis is present. Following I&D in the ED, refer to a surgeon for definitive care.

Hidradenitis suppurativa: a chronic follicular occlusive disease of the intertriginous skin. It usually affects the axillary, groin, perianal, perineal, and inframammary regions and less commonly affects the perirectal area. When it does present in the perirectal region, it will usually be recognized by its typical location in the perineal or inguinal area.

Presentation: inflammatory, solitary, painful nodules are usually the first lesions. Patients may be unable to walk or sit without pain. Sinus tracts, comedones, and scaring can also be present.

· Diagnosis is clinical; typically recognized by characteristic location (axillae, groin), lesions (deep-seated nodules, comedones, sinus tracts) and relapses.

· Small abscesses can be drained in the ED, but extensive lesions require surgical or dermatologic referral. Topical clindamycin or oral clindamycin with rifampin can be helpful.

Differential Diagnosis: other disorders to consider include anal tags, anal stenosis, cryptitis, proctitis, rectal prolapse, anorectal tumors, rectal foreign bodies, pruritis ani

References

1. WikipedianProlific – [1], CC BY-SA3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4953948.)

2. Bernardo Gui – Own work, Public Domain

3. Foxx-Orenstein AE, Umar SB, Crowell MD. Common anorectal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2014;10(5):294‐301.

4. Berberian JG, Burgess BE. Anorectal Disorders. Ch. 85: Anorectal Disorders. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw-Hill;

5. Cruz JY, Sentovich SM. Anorectum. In: Doherty GM. eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery, 15e. Ch. 33. Anorectum. McGraw-Hill;

6. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids: outcome after conservative or surgical management. Greenspon J, Williams SB, Young HA, Orkin BA Dis Colon Rectum. 2004 Sep; 47(9):1493-8.