Want to experience the greatest in board studying? Check out our interactive question bank podcast- the FIRST of its kind here: emrapidbombs.supercast.com

Author: Blake Briggs, MD

Peer Reviewer: Travis Smith, DO; Mary Claire O’Brien, MD

Objectives: Describe the pathophysiology, presentations, diagnoses, and treatments of crystal arthritides, as well as the methods of arthroscopy. Briefly mention Pseudogout.

Introduction

The term gout refers to a spectrum of manifestations that can occur singly or in combination: acute inflammatory arthritis, tenosynovitis, chronic tophaceous arthritis (tophi), extraarticular tophi, urate nephrosis, acute uric acid nephropathy, and uric acid nephrolithiasis. Hyperuricemia is the hallmark of gout. Plasma and extracellular fluids that become supersaturated with uric acid may crystallize and result in clinical gout.

Overall, the incidence of gout has been increasing in the US; its prevalence is likely ~3% total of all adults.

The differential diagnosis for acute gouty arthritis includes septic arthritis, reactive arthritis, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (pseudogout), and rheumatoid arthritis.

Hyperuricemia is necessary for gout to occur, but alone is not enough. In fact, most patients with hyperuricemia do not have gout. Hyperuricemia may arise in a variety of settings that cause overproduction (e.g. cancer, genetic condition) or underexcretion (e.g. kidney disease, certain medications) or a combination of the two.

Lifestyle features that greatly increase the risk of gout include: alcohol consumption, obesity, high purine foods (mussels, shrimp, organ meats), salty fish (sardines, herrings), sausage, red meats

Accelerate your learning with our EM Question Bank Podcast

- Rapid learning

- Interactive questions and answers

- new episodes every week

- Become a valuable supporter

Interestingly, there has been a rise in “non-classic” gout patients, or rather, those who do not fit the classic story for acute gout. These patients are older, more female, possibly a history of an organ transplant receiving diuretics and calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine and tacrolimus impair urate excretion).

Presentation of acute gout flare

Acute gouty flares are exquisitely painful, with redness, warmth, and swelling of the affected joint. Maximum severity is reached in <24 hours. Attacks generally subside spontaneously in a few days.

80% of cases involve a single joint in the lower extremity. Gout flares are twice as likely to begin after sleeping. This is because episodes classically occur at night when the patient is supine. They wake to discover a tender, swollen joint in the most dependent area of the body. Why at night? The temperature drop reduces solubility and promotes crystallization. Therefore, one can expect to find gout flares in the ankle or first metatarsophalangeal joint (known as podagra). The great toe is the first site of attack in half of cases.

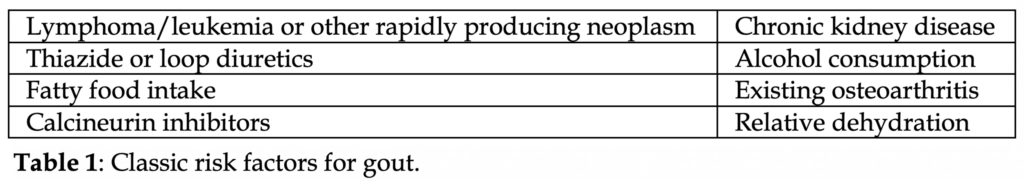

A mess of dietary, physical risks, as well as commodities and medications can predispose to cause a gout flare (Table 1).

In <20% of patients, multiple joints can be affected at once. This polyarticular pattern typically occurs in later flares.

Patients with recurrent gout flares may have solid tissue deposits of urate (tophi) which cause longstanding articular injury. Tophi are not painful nor tender. Tophi gradually increase in size, causing worsening soft tissue and joint injury. In the fingers, it looks like dactylitis.

Also, long term, chronic hyperuricemia causes nephrolithiasis and nephropathy, as urate itself is nephrotoxic.

Diagnosis

The only definitive method of diagnosing gouty arthritis is joint aspiration and demonstration of the characteristic crystals by polarizing microscopy. Who should undergo arthrocentesis? Anyone with suspected gout flare in whom the diagnosis has not been formally made, or those where the cause is uncertain and you need to rule out more serious causes (e.g. septic arthritis).

Cell count, gram stain, culture, and crystal analysis should be performed.

Urate crystals are needle-shaped and negatively birefringent under polarized light microscopy. This means that if shown a picture of the crystals, when they are lying flat they should be yellow (yellow when laying low), and if vertical they should be blue.

The sensitivity of polarized light is 85% with a specificity of 100%.

Labs cannot diagnosis gout. ESR, CRP, and WBC count are worthless for gout, but if you are concerned for septic arthritis that is a different discussion. You could argue what is the point of getting the markers if you are planning to do an arthrocentesis anyway… we would agree with that assessment.

Even worse, we still hear of a lot of people ordering uric acid levels. Please don’t. Those levels don’t correspond to gout flares and they do not change management. Normal serum uric acid levels do not rule out gout.

WBC count can range from above 10,000, but gout should never cause a WBC count above 100,000. If you see that, think concomitant septic arthritis. Gout may coexist with other inflammatory arthritic conditions.

X-rays don’t help diagnose gout. Subcortical bone cysts and erosions might be seen, suggestive of chronic arthropathy.

What if the crystal microscopy is negative? If concern for gout is still high, we recommend close follow up with a PCP and/or rheumatologist. Missing a gout flare isn’t the end of the world, missing something more serious is!

Pseudogout: Calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease is diagnosed when calcium pyrophosphate crystals are demonstrated in synovial fluid analysis. Pseudogout crystals are rhomboid or cuboid shaped and are weakly positive on polarized light microscopy. The KNEE is the most commonly affected joint in pseudogout, followed by the wrist and ankle. Calcium deposits may be seen in the articular cartilage (chondrocalcinosis), but this is not always associated with symptoms. Dietary modifications cannot prevent pseudogout flares. Treatment includes glucocorticoids or NSAIDs.

Treatment

Chronic long term therapy to prevent gout flares and reduce chronic arthropathy include allopurinol, febuxostat, and probenecid. There are a few others that are much less common.

These therapies do NOT help during gout flares, but contrary to current dogma, they are not harmful and should NOT be discontinued.

Acetaminophen and opioids do not help reduce gout inflammation. They can be used as an adjunctive but are not solutions.

Of the three major therapies (NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, and colchicine), there is no single best agent.

The best method is to review the patient’s comorbidities to each medication, their preference (if this is not their first flare), and how adequate is their rheumatology follow up.

For example, if any renal disease is present, you must avoid NSAIDs. Other conditions in which we avoid NSAIDs: known coronary artery disease, peptic ulcer disease, certain anticoagulation medications, or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

Details of dosing

NSAIDs: naproxen, indomethacin, ibuprofen for 5-7 days

-perfect for those <60 years old who lack renal, cardiovascular, or ulcer disease.

Glucocorticoids: 30-40 mg prednisone initial dose with a 7-10 day taper.

-avoid if septic arthritis is a concern!

-great for those where NSAIDs are contraindicated or pregnant patients

-caution in those with brittle diabetes, recurrent steroid usage

Colchicine: 0.6 mg pill formulation. Patient cannot exceed 1.8 mg in 24 hours.

-should really only be used if the above two options are unavailable.

-convenient for patients who have been on it before or taking it for flare prophylaxis

-significant side effects if taken incorrectly, low dose therapy only.

–must be started within 36 hours or else benefit of therapy is minimal.

-contraindicated in those with severe renal or hepatic impairment, or those on significant cytochrome P450 inhibitors.

-diarrhea and abdominal cramping are the most common side effect. They are less likely at lower doses.

-more serious adverse effects are typically seen at high doses and include neutropenia, bone marrow suppression, and peripheral neuropathy.

In those with established chronic gout limited to one or two joints, we can refer these patients for outpatient intra-articular steroid injection.

References

1. Loeb JN. The influence of temperature on the solubility of monosodium urate. Arthritis Rheum 1972; 15:189.

2. Nakayama DA, Barthelemy C, Carrera G, et al. Tophaceous gout: a clinical and radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum 1984; 27:468.

3. Lawry GV 2nd, Fan PT, Bluestone R. Polyarticular versus monoarticular gout: a prospective, comparative analysis of clinical features. Medicine (Baltimore) 1988; 67:335.

4. Lin HY, Rocher LL, McQuillan MA, et al. Cyclosporine-induced hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:287.

5. Burack DA, Griffith BP, Thompson ME, Kahl LE. Hyperuricemia and gout among heart transplant recipients receiving cyclosporine. Am J Med 1992; 92:141.

6. Juraschek SP, Miller ER 3rd, Gelber AC. Body mass index, obesity, and prevalent gout in the United States in 1988-1994 and 2007-2010. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65:127.

7. Gutman AB. The past four decades of progress in the knowledge of gout, with an assessment of the present status. Arthritis Rheum 1973; 16:431.

8. Hunter DJ, York M, Chaisson CE, et al. Recent diuretic use and the risk of recurrent gout attacks: the online case-crossover gout study. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1341.

9. Neogi T, Chen C, Niu J, et al. Alcohol quantity and type on risk of recurrent gout attacks: an internet-based case-crossover study. Am J Med 2014; 127:311.

10. Dalbeth N, Haskard DO. Pathophysiology of crystal-induced arthritis. In: Crystal-induced Arthropathies, Wortmann RL, Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Ryan LM (Eds), Taylor & Francis, New York 2006. p.239.

11. Hadler NM, Franck WA, Bress NM, Robinson DR. Acute polyarticular gout. Am J Med 1974; 56:715.

12. Raddatz DA, Mahowald ML, Bilka PJ. Acute polyarticular gout. Ann Rheum Dis 1983; 42:117.

13. Gutman AB. Gout and gouty arthritis. In: Textbook of Medicine, Beeson PB, McDermott W (Eds), Saunders, Philadelphia 1958. p.595.

14. Dalbeth N, Kalluru R, Aati O, et al. Tendon involvement in the feet of patients with gout: a dual-energy CT study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72:1545.

15. Pascual E, Batlle-Gualda E, MartÃnez A, et al. Synovial fluid analysis for diagnosis of intercritical gout. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131:756.

16. Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum 1977; 20:895.

17. Chen LX, Schumacher HR. Current trends in crystal identification. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006; 18:171.

18. Neogi T. Clinical practice. Gout. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:443.

19. Terkeltaub R. Update on gout: new therapeutic strategies and options. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010; 6:30.

20. Sundy JS. Progress in the pharmacotherapy of gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010; 22:188.

21. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:1312.

22. Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of Acute and Recurrent Gout: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166:58.

23. Sutaria S, Katbamna R, Underwood M. Effectiveness of interventions for the treatment of acute and prevention of recurrent gout–a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006; 45:1422.

24. Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ 2002; 324:1488.

25. Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, et al. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum 2010; 62:1060.

26. Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet 2008; 371:1854.

27. Zhang YK, Yang H, Zhang JY, et al. Comparison of intramuscular compound betamethasone and oral diclofenac sodium in the treatment of acute attacks of gout. Int J Clin Pract 2014; 68:633.

28. Colchicine and other drugs for gout. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2009; 51:93.

29. Harrison’s Manual of Medicine, 16th edition. Editors: Dennis L. Kaspar, et al. The McGraw-Hill Companies. 2005.